Ecosia is a search engine that uses profits to plant trees

For every 45 inquiries conducted on its search engine, Berlin startup Ecosia has a seedling planted somewhere on the world

At first glance, the Berlin startup doesn't seem so different from others: a factory floor in the rear courtyard of a building in the city's Neukölln district, stacked preserving jars filled with muesli in the kitchen, a discarded ping-pong surface repurposed as a conference table. The employees are young, relaxed and very international.

The company's head and founder, Christian Kroll, is 35 years old, the same age as Mark Zuckerberg. The two men also share a quirk: To avoid wasting time in the mornings choosing an outfit, he always wears the same thing -- in his case, blank white T-shirts made from organic cotton. Zuckerberg's favorite color, by contrast, is gray. But that's where the similarities end.

Kroll is no traditional startup founder, and Ecosia isn't a company that operates according to tech-sector rules or capitalist textbooks.

For one, he managed to build up a search engine in several languages with sales in the double-digit millions that is also profitable -- and even pays the appropriate local taxes.

The company's actual goal isn't to enable people to search and find things online. That is merely a means to an end. Kroll claims not to care about classic indicators of success in his sector -- income, bonuses, going public or other lucrative ways of making an "exit" from a company. "I want to bring forth social change," he says. For Kroll, it's about growth -- literally.

Ecosia is about trees. Kroll wants to save them, and plant new ones. As many as possible, as a natural contribution to climate preservation, since trees absorb climate-damaging CO2.

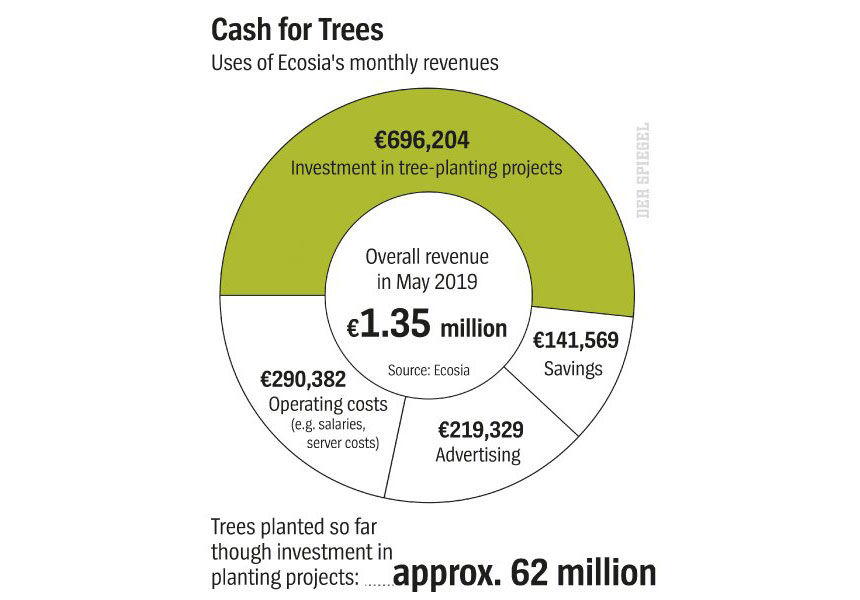

Kroll's ecological business model is simple: As with other search engines, advertisements are served to Ecosia users alongside their results. The company's revenues -- after salaries, costs for travel, servers and marketing as well as savings are subtracted -- flow into projects run by more than 20 partner organizations focused on reforesting in countries like Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Indonesia and Brazil.

Ecosia's website, which is as pared-down as Google's, has a tree counter: At the middle of last week, it stood at over 62 million newly planted trees. For around every 45 searches, a new seedling is planted. It's about clicking to save the climate. A user's personal plant count is shown on the top right.

A Timely Idea

All this sounds a bit too simple to be true, like a genius marketing idea in a time in which companies are announcing plans to operate CO2 neutrally in the future and are at times carrying out absurd attempts at "greenwashing." It seems to be a perfectly designed business model for a society in which hundreds of thousands of students protest every Friday to stop climate change and in which a non-fiction book by a forester about the secrets of trees is a bestseller.

But Ecosia will turn 10 years old in December. Kroll was born in Wittenberg, a city in the eastern German state of Saxony-Anhalt, and moved to Berlin in his mid-twenties to, along with his sister, turn his idea of an ecological search engine into reality. At the time, the green tech movement hadn't really taken off yet.

The fact that Kroll was such a forerunner can also be traced to the fact that he is as much an activist as he is a businessman. It is his view of the world that drives him, and it is a grim one: "If we want to survive the 21st century, then we need to reforest on a massive scale."

Kroll sees trees as an "all-purpose weapon, a perfect technology by mother nature." He argues they provide people in previously desolate areas not only with fruits, nuts and a more pleasant micro-climate, but also raise the water table and, above all else, remove CO2 from the atmosphere. According to Kroll's calculations, even if all countries abide by the climate goals of the Paris agreement, a trillion new trees around the world would be needed to lower CO2 levels in a significant way.

The founder bases his argument on, among other things, a recent study by ETH Zurich University that describes reforestation as the most inexpensive and effective method for saving the climate. A trillion trees. Is that not utopian in a time in which a net 10 billion trees vanish every year? "If Ecosia made as much profit as Google," Kroll says, soberly, "we could plant the trillion trees on our own over the next 20 years."

Kroll got interested in computers at a young age -- and in how to make money from them. He sold CD-ROMs in his schoolyard, and soon became fascinated by the stock market. As a teenager, he closely followed the boom in the Neuer Markt, a segment of the German stock market focusing on New Economy companies in the 1990s, and bought his first stocks. "For a time, I invested in a Ukrainian oil company and in a Georgian supermarket company," he says, smiling. Kroll seemed to be on a path to becoming an investment banker. He moved to Nuremberg to study business administration because it was home to renowned financial market experts.

He says his conversion from economist to ecologist happened when he was at college. With his thesis packed in his luggage, he flew to Kathmandu and traveled to Mount Everest base camp. In Nepal, he tried to build his first search engine as a "social project" with local employees. He set up his office between two neighborhoods because there was often only electricity in one of the two. "There was barely any internet, hardly any electricity, there were cultural barriers and the project ended quickly," he recalls.

At some point, he read Thomas L. Friedman's bestseller, "Hot, Flat and Crowded," which called for a "green revolution." One figure from the book stuck in Kroll's head: That 20 percent of CO2 emissions can be traced to deforestation.

In 2008, he founded Forestle, his first green search engine. The last two letters were an homage to Google, which initially partnered with Kroll, only to end the collaboration a few days later by email. It accused Forestle of encouraging its users to click on ads they weren't necessarily interested in to maximize donations, which violated the company's rules. Kroll wrote on the Forestle website at the time that the project seemed to have become too successful too fast for market leader Google.

To this day, he doesn't speak positively of the tech giant and its "dangerous global power," even if he says he has "enormous respect, because they are simply very smart." His follow-up project, Ecosia, follows a similar principle -- his company didn't develop the search algorithms either. The Berlin company uses the technology behind Microsoft's Bing, which is also handles the advertising and ensures good search results.

German consumer watchdog Stiftung Warentest recently ranked Ecosia as the third best search engine in Germany after Startpage and Google based on quality of results, ease of use and privacy policies.

Advertising revenues are split between Bing and Ecosia. Kroll won't reveal the exact cut, but he says the "biggest portion" remains with the Berlin-based company.

Radical Transparency

Otherwise, his company is unconventionally transparent when it comes to its finances. Every month, the search engine company posts a financial report online that shows its revenues and overhead costs, as well as the amount Ecosia passes on to projects. In May, its overall income was 1.35 million euros, of which around 696,000 euros flowed into reforestation projects.

Last year, the founder and his long-time partner, a serial startup founder from Cologne and veteran in the tech sector, went a step further in their effort to dispel any doubts about their motives. They transferred 99 percent of their company capital and 1 percent of the company's voting rights to the Purpose Foundation in Switzerland.

It monitors the company to ensure they don't pay themselves dividends or sell their stock to third parties outside the company. If either was to take place, the foundation would have a responsibility to use a veto. According to the most recent Ecosia numbers, this means the two have forsaken many millions of euros by taking this approach, essentially giving away their own company. The company now basically belongs to itself. The step, Kroll says, is "irreversible and legally binding." He says he also wanted to plan for the possibility that he might die and that his heirs would need to sell the company because of inheritance tax.

But who checks to ensure that Ecosia's partners work cleanly and use the donations as promised? And whether the trees grow and thrive instead of just wasting away as seedlings?

That's Pieter van Midwoud's job. The Dutchman might even have the best position at Ecosia. He calls himself the "tree-planting officer." His work entails comparing satellite images and collecting proof in the form of digital photos. He also travels to the sites of many projects himself and returns with videos that Ecosia then posts on its website as "tree-planting updates."

Making a Name

When it comes to advertising itself, Ecosia has been making a considerable effort recently. Employees in company T-shirts protested the impending deforestation of the Hambacher Forst, a forest in western Germany that was in danger of being cut down as part of operations at an open pit mine owned by the utility giant RWE. The company also came up with the idea of offering RWE's CEO a million euros to buy the remaining forest.

Kroll is also known to bike alongside the student demonstrators of Fridays for Future protests with his own sign. The movement is a blessing for the company. Its participants are young and, as such, the ideal target group. In May, Kroll got invited to come on stage at the protest, and he donated a tree for each of the 25,000 protesters -- 25,000 mangroves for Madagascar.

Companies are now also getting involved: German wholesale store chain Metro, for example, announced this past autumn that it would install Ecosia as the standard search engine at its company headquarters, and that it planned to roll it out for all 150,000 of its employees worldwide. Of course, it doesn't really cost the company much and it is difficult to verify.

Kroll admits that critical questions have been raised by employees about certain marketing ideas, but he argues that one needs to use every opportunity to raise one's profile: "We are the David in this game, and we cannot act entirely ideologically."

With the growing numbers of users and increasing visibility, critical questions from outside are also on the rise -- about the company's own carbon footprint, for example. The internet, after all, is responsible for a considerable proportion of global CO2 emissions, and that amount is growing. And, unlike Google, which claims it has bought as much renewable energy since 2017 as it uses in electricity, Ecosia partner Microsoft only claims that it will reach 70 percent green energy by 2023.

But Ecosia has taken action on its own to become an energy supplier. This past year, the company began operating its own solar-power plant in Germany's Ore Mountains region, and a second has just gone online in the state of Saxony-Anhalt. The plants' electricity production has already exceeded the company's own needs, Kroll says, and they are also generating additional profits.

Thus far, of course, Ecosia's contribution to climate protection has been small. And its global share of the search-engine market is at "over 0.1 percent," and at about 1 percent in Germany. Kroll and his employees want to use the green wave to grow. At the same time, they will have to swiftly develop new technologies.

The trend, Kroll says, is moving away from traditional search engines toward digital personal assistants. His vision for Ecosia, he says, is that of a digital adviser who helps a person live a more environmentally friendly life. Users looking for a flight from Berlin to Munich, for example, would automatically also be shown train connections, as well as a figure showing how much CO2 the alternative would save. Ecosia software developers are also working on a maps application that will promote "green locations" and will not "track every movement" on a person's phone.

Kroll says the idea of green living needs to be made more attractive, but that with only a few years left to go, it will likely be impossible to prevent a climate catastrophe without banning certain things. Ecosia's own internal debates are indicative of just how challenging this will be. The company had considered banning Ecosia employees from flying, but that idea has since been shelved. The company has employees from 17 nations, and the projects it finances need to be supervised.

Kroll himself also regularly completes a CO2 statement alongside his tax return. Two years ago, he visited a planting project in Indonesia, he said he is still paying off his climate debt. This summer, he'll be traveling to southern France. By train.

Thanks to Spiegel